>> Digital Deconstruction of Human Rights

click here for a plain text file of this page →

This project critiques human rights as framed by the UN Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) from 1948. Through a collection of text data about human rights, the imagery and various contexts, this project encourages the viewer to question “who has power to declare rights?” and “who can claim rights?” in a critique of the uneven distribution of rights and the antiquity of certain rights around the world today.

While the UDHR is and has been used in liberatory movements and to work towards a fair, dignified, equal treatment of individuals and communities around the world, these same rights are a political tool that has also been used to justify imperialism, violence, and more. The UDHR can be seen as a political tool by its framing of the rights and freedoms of individuals in relation to the nation-state. For example, Article 9 states that “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.” Here, and in many other rights from the UDHR, the nation-state is “paradoxically the perpetrator of human rights violations and the body through which rights and freedoms are given to people” (source: Human Rights and Computation Course UAL CCI MA Internet Equalities, Cindy Ma) This project is a “deconstruction” of this framing by exploring the ideas that technologies, individuals, nature, and corporations can also be granters and violators of human rights.

‘DDHR’ is a text data project to enhance awareness of the unevenness of human rights in specific contexts, and their entanglements with corporations and technologies through time.|

project process

This project originated in February 2022 with the prompt to create a prototype of a data-driven artefact that explores bias in AI or other computational inequality. The Digital Deconstruction of Human Rights explores the social issues raised by human rights in the digital age using multiple text datasets.

Over this process, I heard from family and friends about the “Freedom Convoy” protest in Canada, where people claim human rights violations for vaccine mandates and border-crossing rules. I heard about the Tigray War, the Russia-Ukraine war on Twitter, and I watched these topics, and their entanglements with human rights, take over the headlines and conversations in my circles. It became clearer that some voices are a lot louder than others when speaking about human rights, which led me to think about who can claim human rights, who is more human than who, and who and what can control human rights.

Twitter text data in this project was “scraped” selectively. There is hate speech on Twitter, and it did not to be included in this project. Embedding harm such as racism, sexism, hate speech, and other biases is not a new issue with data-based projects. Specifically on Twitter, Microsoft’s Tay chatbot, “TayTweets,” was an example of what could go wrong with using data from Twitter.

Context: “In 2016, Microsoft’s Racist Chatbot Revealed the Dangers of Online Conversation The bot learned language from people on Twitter—but it also learned values” (source: https://spectrum.ieee.org/in-2016-microsofts-racist-chatbot-revealed-the-dangers-of-online-conversation)

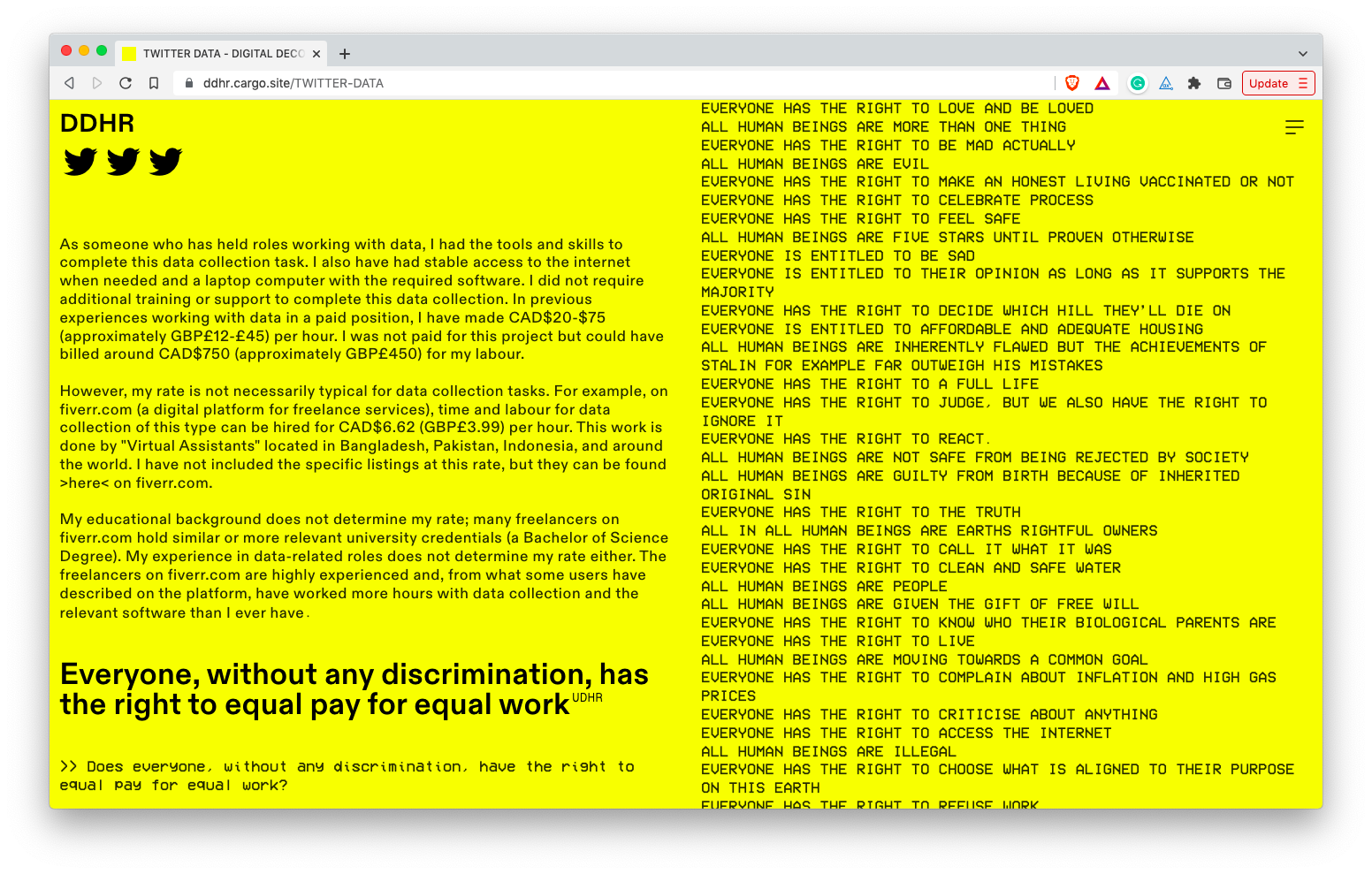

Originally this project was going to generate “human rights” by fine-tuning GPT-2 to generate context relevant text, based on the data scraped from Twitter. However, as I continued to collected the data from Twitter and started playing around with text generation using GPT-2 and transformers, I noticed that some statements from Twitter and some statements generated with GPT-2 were very similar. Additionally, when reading some of the Twitter-claimed rights, I agreed with sentiment some of them (Everyone is entitled to health care, Source: Twitter, Date: 2/17/2022) and I noticed that many of the rights were supported by others. I understood support on Twitter as demonstrated by likes, retweets, and comments on the post. Another important consideration is that I had no way of knowing if a person authored the tweet or if a bot did. Because of the potenial overlap of computer generated statements, the fact that I could not know if a person had shared the tweet, and the courious similarity, I decided to not continue with fine-tuning GPT-2 to generate text data.

The text data from Twitter, GPT-2, and UDHR was “cleaned,” meaning that it was modified for conformity and exportability, using Google Sheets. This tool was chosen because of my previous knowledge and experiences with Excel functions, the ease of export, and the way that I can share a viewable link publicly.

Missing from this project are Tweets in languages besides English. While users from many places around the world can Tweet in English, many voices and opinions are not part of this project. Furthermore, all perspectives and voices that do not share specific views and statements about rights on Twitter are not included. These are some of the loud voices, but these voices often speak over others. As this project is to create a discussion about human rights, I hope it can create space for more perspectives and more voices to be listened to.